Status Management

Monday, June 10, 2019

I learned about “status management” recently while reading Daniel Coyle’s The Culture Code. Since then, I can not stop noticing status management.

Unfortunately, as we are always going through change, as our work interactions are turning more and more fluid, and as role/responsibility boundaries are getting blurrier, “status management” is becoming an epidemic in most work interactions. Our reactions are often motivated by how each of us wants to “fit in”, which is an individual objective in the emerging status and not necessarily on how to impact the change, which is a group objective. In these cases, status management decides what an individual says or does. We see plenty of examples at work or on social media, of people giving opinions which are often designed to maximize their “status”. Decoupling oneself from their intended status during a change is hard and yet essential to inflict the shift.

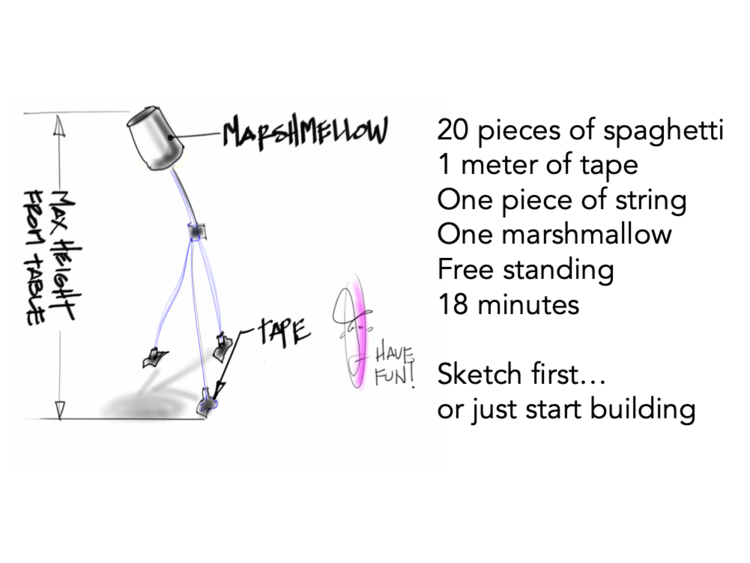

Daniel introduces status management through a case study of how two groups, a group of kindergartners and a group of business students, conduct themselves in Peter Skillman’s Spaghetti Tower Design challenge. This is a fairly common challenge used for team building.

You can read an excerpt from this part of the book on Daniel Coyle’s website, but let me share the part that stuck with me.

The business school students appear to be collaborating, but in fact they are engaged in a process psychologists call status management. They are figuring out where they fit into the larger picture: Who is in charge? Is it okay to criticize someone’s idea? What are the rules here? Their interactions appear smooth, but their underlying behavior is riddled with inefficiency, hesitation, and subtle competition. Instead of focusing on the task, they are navigating their uncertainty about one another. They spend so much time managing status that they fail to grasp the essence of the problem (the marshmallow is relatively heavy, and the spaghetti is hard to secure). As a result, their first efforts often collapse, and they run out of time.

In the rest of the book, Daniel walks through the skills necessary (such as building safety, sharing vulnerability, and establishing purpose), to help “tap into the power of our social brains to create interactions exactly like the ones used by the kindergartners building the spaghetti tower.”

The trick, I think, is being okay not to have a status in the change, and yet be willing to influence or even lead the change. This requires that you feel safe that your job is not at risk even if you have no status in the change, or you trust your ability to find something else to do. This ability is one of the essential characteristics of growing as a leader. Not having status is not a failure.